Cross-validating Time Series

TL;DR

Using classic k-fold CV to evaluate an ML model on time series data can produce incorrect results due to look-ahead bias. Instead, consider walk-forward validation, which is (probably) the safest evaluation method for time series data. However, the optimal choice will depend on your data and model (you may want to check the article below).

Can we cross-validate a time series?

Data scientists cross-validate everything. This is just the natural order of things. Unless you are dealing with neural networks, which are notoriously difficult to fit even once (let alone k times), the chances are that you use CV 10 times out of 10.

The good old k-fold CV is great. It's intuitive. It has a solid 50-year track record. It's implemented in every mainstream language. It's backed up by theory: it's guaranteed to give a consistent estimate of an out-of-sample error with lower variance than a single train-test split. But there is a catch: most theoretical results regarding CV assume that our data is i.i.d. (for example, see [Bayle2020]). What if you're dealing with time series data?

Knowing the future

Time series data is not i.i.d. Data samples from different time periods may produce different model weights during training and show different model errors during testing. In particular, if you train on data from a later period ("the future") to evaluate model performance on data from an earlier period ("the present"), you may see an optimistic (= unrealistically small) out-of-sample error estimate. This phenomenon is called look-ahead bias. Classic k-fold CV is prone to this problem.

But does the future always hide something of a particular value? In other words, when does look-ahead bias matter? To answer that, we need to dive deeper into the world of probability and statistics.

Stationary processes

A data generation process is usually assumed to follow some sort of a rule regarding how the data distribution can change over time. Without this assumption, we have no hope of drawing any meaningful conclusions about the future. Imagine that a vitamin D supplement that boosts a patient's immune system can suddenly become absolutely inefficient with no observable change in the patient's biochemistry, their intake of other drugs, their environment, etc. In this case, it would be impossible to accurately evaluate its impact on the patient's health and determine the optimum daily dosage for the next month today.

One common assumption is that a data generation process is (weakly) stationary - i.e., covariance between two data points depends only on a time interval between these two points. Speaking broadly, a stationary process can only evolve over time in a very limited way. Common examples are white noise and the ARMA process.

There are many theoretical results related to such processes. In particular, stationary processes seem to be less affected by look-ahead bias. [Bergmeir2012] numerically compares different model error evaluation methods on stationary data and concludes that k-fold CV is a viable option to use for out-of-sample error evaluation and hyper-parameter tuning of ML models. [Bergmeir2018] theoretically proves that this is the case for autoregressive models.

On the other hand, [Schnaubelt2019] numerically demonstrates that k-fold CV can be an inadequate choice for non-stationary processes. Okay, so what can we use instead?

Note: Sometimes we can transform data to make a process stationary. Two common cases are removal of seasonality and trend, which we won't cover here.

Evaluation methods for time-series: pros and cons

Surprise, surprise: I wasn't the first to think about the potential issue of look-ahead bias for time series data! People invented a bunch of different evaluation methods. Here are some of the most popular ones:

- Single split (a.k.a. last block validation)

- Walk-forward validation

- Moving-origin forward validation

- Blocked k-fold CV

- Combinatorial CV

All these methods split time series data without shuffle. Where applicable, the data points before and after a split point are referred to as the "past" and the "future", respectively.

1) Single split (a.k.a. last block validation) divides time series in two parts: the "past" (used for training) and the "future" (used for validation).

Pros:

- Cheap to compute

- No look-ahead bias

- Easy to use with sequential models (e.g., State Space and RNN)

Cons:

- It cannot evaluate the earliest period of the history

- High estimate variance because only one block is used for testing

2.a) Walk-forward validation makes several splits of time series into the "past" and the "future", progressively moving the split point from earlier to later dates. The most "classical" approach uses an expanding window for the training set and a fixed-size window for the validation set but other methods are used as well. Unlike CV, WF validation never uses data from the "future" for training. There are several modifications of WF validation: for example, see [Tashman2000].

Pros:

- No look-ahead bias

- Easy to use with sequential models (e.g., State Space and RNN)

Cons:

- It cannot evaluate the earliest period of the history

- A pessimistic estimate bias because the size of the training set is growing over time

2.b) Moving-origin forward validation is a modification of WF validation that uses an expanding window for both training and validation sets (i.e., all data is used in every split).

Pros (w.r.t. WF validation):

- The more recent data is evaluated more, so its contribution to the overall result is higher

Cons (w.r.t. WF validation):

- A more pessimistic estimate bias because almost half of the folds have a validation set bigger than a training set, which is unlikely to produce a robust estimate

3.a) Blocked k-fold CV is almost like classic k-fold CV but data is not shuffled. Instead, data is split in k continuous blocks. If one block is left out for validation then the rest are used for training. This allows us to partially preserve the sequential nature of times series.

Pros:

- The same amount of data points in every training set

- It can evaluate the earliest period of the history

Cons:

- Look-ahead bias

3.b) Combinatorial CV (the term coined in the book [Lopez2018]) is a more "sophisticated" cousin of blocked k-fold CV. Like before, data is split in k continuous blocks but p blocks (1≤p≤k) can be selected for testing at once. This produces more data splits, which may be useful for algorithmic strategy backtesting as we can generate several backtest paths at once.

Pros (w.r.t. blocked k-fold CV):

- It generates several backtest paths rather than one

Cons (w.r.t. blocked k-fold CV):

- A few times more computationally expensive

Empirical study

Good, we have plenty of validation methods to choose from. So, which one to choose? Well. We could rely on conclusions from the papers referenced above or... we could test them ourselves! I made a jupyter notebook with a comparison of different validation methods on synthetic time series data. I tested linear and non-linear models on stationary and non-stationary time series data. Since I generated data myself I was able to make multiple data simulations to obtain the mean and standard deviation of model error estimates.

Here are some of the findings.

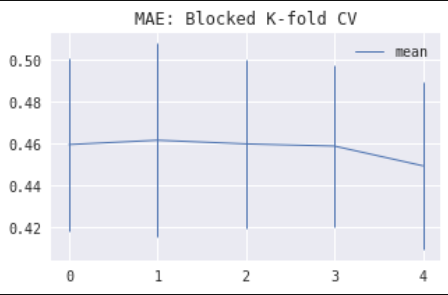

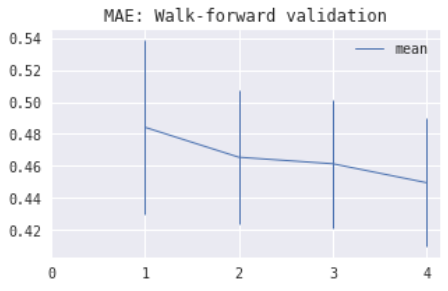

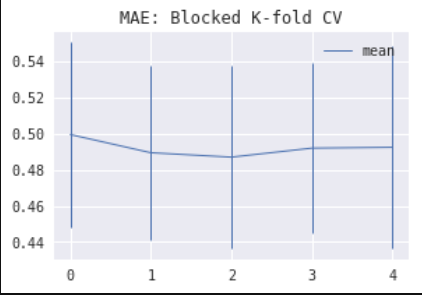

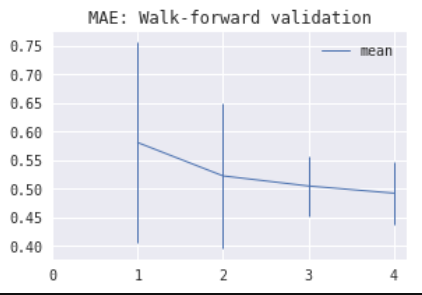

1) For stationary processes, blocked k-fold CV is generally superior to WF validation, showing smaller bias and variance for earlier folds. The images below show estimated model MAE (= median average error) by fold using CV (left) and WF validation (right) for Linear Regression on an ARMA time series.

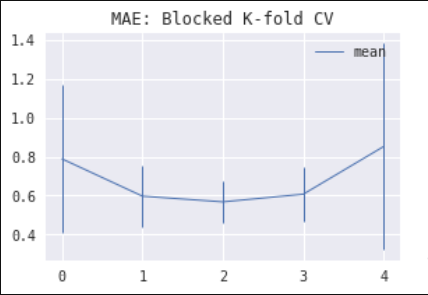

2) For non-stationary processes with a stochastic mean drift, blocked k-fold CV produces an interesting result: the error estimate is lower in the inner folds. This effect is especially noticeable for models with an intercept (this includes Gradient Boosted Trees which have an implicit "intercept" term). Intuitively, the simplest fold to predict (if any) should be either the first one (because our pesky drift impacted it the least) or the last one (thanks to the longest available history to learn from). So why? The reason is that the information about the realized drift can be learned by an intercept term more efficiently in the middle fold, where it becomes a problem of interpolation rather than extrapolation. Hence, we get an optimistic bias in a model error estimate. The images below show estimated model MAE by fold using CV for Linear Regression with an intercept (left) and Gradient Boosted Trees (right) on an ARMA time series with a stochastic trend.

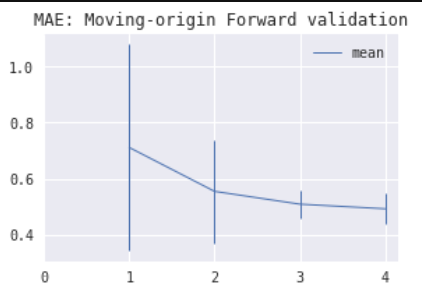

3) Walking-origin forward validation often has a significantly higher model error estimate variance for earlier folds compared to WF validation. Therefore, its usability is doubtful. The images below show estimated model MAE by fold using walking-origin forward validation (left) and WF validation (right) for Linear Regression with an intercept on an ARMA time series with a stochastic trend.

4) Combinatorial CV produces either exactly the same or very similar results compared to blocked k-fold CV. So you can use it instead of blocked k-fold CV if you want to see multiple backtest paths for your trading strategy.

Bias vs variance

There is one more thing to consider. Let's take MSE as our model error. Then we can compute the difference between the real MSE and our estimate (for example, computed via CV) as

A look-ahead bias will be the part of the bias term. Now, why do you need to estimate out-of-sample model error? If the goal is...

- evaluation of out-of-sample model performance ⇒ bias is crucial (for example, we definitely don't want to launch a trading strategy based on an optimistic estimate)

- model hyper-parameter tuning ⇒ bias is non-essential if it's consistent across all hyper-parameters

Thus, it may be okay to have a look-ahead bias for model hyper-parameter tuning. There, we can focus on the variance of our estimate. Concerning our empirical study, this means that CV might be a preferable method for hyper-parameter tuning even when we see that the error estimate in the inner folds is optimistic. However, as [Schnaubelt2019] shows, this is not always the case.

Wrapping things up

Dealing with time series data is tough. If you have a limited amount of data and don't use it efficiently, you risk getting a very volatile estimate. On the other hand, if you aren't careful you can be impacted by look-ahead bias and get a rather optimistic estimate. So selecting the right evaluation method is essential. My default method is WF validation, which should be a solid choice for most situations.

Still, the optimal choice depends on your model and data. Here is my humble advice based on the findings above:

- Go with blocked k-fold CV if your time series is stationary, especially if you have a limited amount of data. Here, look-ahead shouldn't be a big problem, and you'll be able to use absolutely all your data for model evaluation.

- Go with WF validation if your time series is (possibly) not stationary, especially if your goal is to evaluate the real out-of-sample model performance. Here, CV is definitely not safe to use as look-ahead bias may have a sizable impact on your estimates.

- Go with WF validation if you're using a sequential model (e.g., RNN or State Space). These models are susceptible to look-ahead bias; also, it's just more straightforward to evaluate them on the "future" data.

- Maybe go with blocked k-fold CV if your time series is not stationary but your goal is to tune model hyper-parameters, especially if you think that your model should not be significantly impacted by look-ahead bias (e.g., it has no intercept term).

- Treat your evaluation method as yet another hyper-parameter to optimize if you have plenty of data and time for your experiments, and (just a tiny bit of) perfectionism disorder.

Keep in mind that evaluation is only one of the many parts of your data analysis. If you strive for robust and realistic results, you may want to check...

- this (rather technical) notebook showing how easy it is to overfit a model using CV; and

- this short article exploring other most common pitfalls in experiment design.

That's it for today! Evaluate your models responsibly. And if you got any comments or questions - please don't hesitate to drop me a message.

References

- [Bayle2020] Bayle, P., et al., 2020. Cross Validation Confidence Intervals For Test Error.

- [Tashman2000] Tashman, L.J., 2000. Out-of-sample tests of forecasting accuracy: An analysis and review.

- [Bergmeir2012] Bergmeir, C., Benítez, J.M., 2012. On the use of cross-validation for time series predictor evaluation.

- [Bergmeir2018] Bergmeir, C., et al., 2018. A note on the validity of cross-validation for evaluating autoregressive time series prediction.

- [Schnaubelt2019] Schnaubelt, M., 2019. A comparison of machine learning model validation schemes for non-stationary time series data.

- [Lopez2018] Lopez de Prado, M., 2018. Advances in Financial Machine Learning.

TODO

I strongly suspect that this will never be done. Yet, it'd be good to expand my experimental study and...

- check the impact of embargoing and purging

- check efficiency of bootstrapping

- test more non-stationary time series

- test Seasonal-Trend Decomposition and State Space models

- run experiments on real-world UK power data